In a digital-first economy, are your data practices built to protect the most vulnerable kind of data? While businesses focus heavily on data-driven growth, there’s a category of information that demands extra caution: sensitive personal information. This data can cause serious harm if mishandled.

But what makes certain data more sensitive than others? Why are governments, regulators, and privacy advocates placing this category at the centre of enforcement? Understanding the legal, ethical, and operational implications is not optional; it’s a business imperative.

This blog explores what qualifies as sensitive personal information, how it differs from general personal data, the global legal frameworks surrounding it, and actionable steps businesses must take to handle it responsibly. Read on!

Sensitive personal information (SPI) refers to data that reveals intimate aspects of an individual’s identity. These include:

Unlike general personal data, like names or email addresses, this information can lead to discrimination, reputational harm, or even identity theft if exposed.

| Criteria | Personal Information (PI) | Sensitive Personal Information (SPI) |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Any information that can identify a person | Data revealing intimate or protected aspects of identity |

| Examples | Name, email, phone number, IP address | Health data, biometrics, race, sexual orientation, geolocation |

| Risk if Exposed | Low to moderate | High (identity theft, discrimination, profiling) |

| Legal Classification | Covered by general data privacy laws | Requires higher safeguards under GDPR, CPRA, VCDPA, LGPD, etc. |

| Consent Requirements | Often implied or opt-out | Explicit opt-in is often required |

| Processing Restrictions | Less restricted (with a lawful basis) | Strongly restricted; must have a legal basis and justification |

| Impact on Rights & Trust | Less likely to cause reputational damage | Significant impact on individual rights and business reputation |

This category of data is labelled differently across global privacy jurisdictions worldwide:

Each law sets stricter rules for processing this type of data, including enhanced consent and data minimisation requirements.

Sensitive data, when exposed, misused, or breached, can result in irreversible and widespread damage:

These risks make it essential for lawmakers to enforce tighter protections.

Even if SPI is anonymised, advances in data science and AI make re-identification increasingly possible. A 2024 study from the UK’s Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) highlights how anonymised location data can be reverse-engineered to identify individuals.

SPI allows businesses and governments to create detailed profiles of individuals, often without their full awareness. This kind of surveillance fuels public distrust and invites regulatory scrutiny.

The General Data Protection Regulation classifies SPI as “special category data” and restricts its processing. Businesses must:

Failure to comply can result in fines up to €20 million or 4% of global turnover.

Across the United States, SPI classifications differ significantly between states and regulatory frameworks:

Each law gives consumers more control over how their SPI is used.

While the U.S. lacks a federal privacy law, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) steps in via its unfair and deceptive practices authority. In the Kochava case, the FTC sued a data broker for selling geolocation data linked to sensitive locations like clinics and places of worship.

India’s DPDP Act (2023) does not create a separate SPI category but still requires lawful and fair processing. Brazil’s LGPD aligns closely with GDPR and includes SPI under its “sensitive personal data” definition, requiring explicit user consent for processing.

SPI directly relates to personal dignity, autonomy, and human rights. Historical abuses, like state surveillance of religious or political groups, have prompted modern legal safeguards. The GDPR, for instance, was influenced by Europe’s past misuse of sensitive data.

Almost 92% of consumers believe businesses must do more to protect highly personal data. Trust is now a key business differentiator.

From GDPR fines to U.S. class-action lawsuits, mishandling SPI comes with financial and reputational consequences. Companies like Facebook and TikTok have faced investigations and penalties for improper use of biometric and geolocation data.

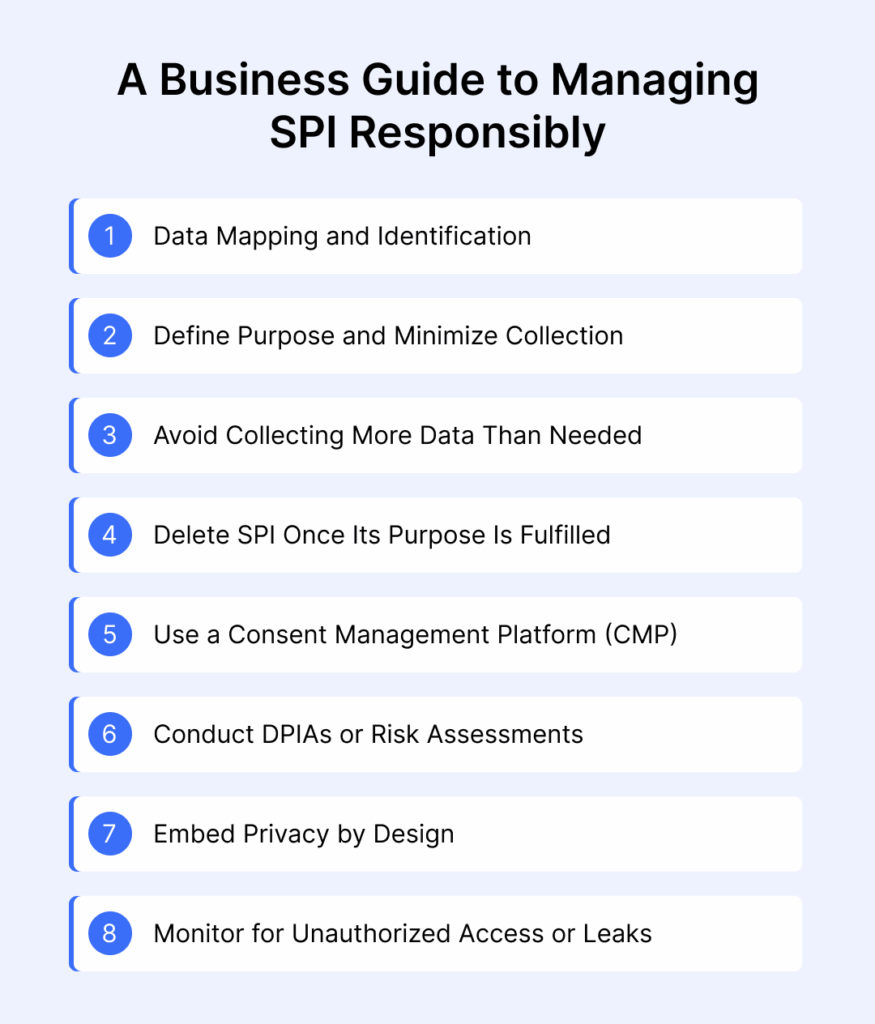

First, identify where sensitive personal information resides in your ecosystem. Use data mapping tools to:

Only collect SPI when absolutely necessary. Ensure you have a clear, lawful purpose and:

Design your consent experience to meet legal standards:

Under GDPR and U.S. laws like VCDPA, businesses must:

Build SPI protections into your systems from day one:

Mishandling sensitive personal information can destroy trust, invite legal action, and derail compliance programs. As global laws become stricter, SPI will stay in the regulatory spotlight.

Now is the time for businesses to assess their SPI practices. Don’t wait for a breach or investigation to get serious about SPI. The cost of inaction is too high.

Audit your data flows, redesign consent mechanisms, and embed privacy into the core operations of your business, across systems, teams, and workflows.

Take the guesswork out of compliance. Use Seers Ai, the AI-driven consent management platform, to automate consent, map SPI, and meet global privacy laws—efficiently and effectively. Don't wait to start the compliance journey.

Start Free NowWatch A DemoNot usually. IP addresses are generally classified as personal information under laws like GDPR and CCPA, but not as sensitive personal information. However, if combined with other data (e.g., health or location data), they can contribute to profiling, raising regulatory concerns. Context matters when determining sensitivity

Only under specific legal bases. For example, under GDPR, storing SPI without consent is allowed if it’s necessary for legal obligations, vital interests, or public interest. But in most scenarios, explicit consent is required, especially for marketing or profiling. U.S. state laws like VCDPA also require opt-in consent before processing SPI

Sensitive personal data should only be retained for as long as it’s necessary to fulfil its intended purpose. GDPR’s data minimisation principle requires organisations to set clear retention periods and securely delete SPI once it’s no longer needed. Retaining SPI “just in case” is a violation in most privacy frameworks.

Penalties vary by jurisdiction. Under GDPR, fines can reach €20 million or 4% of global revenue. In the U.S., states like California can impose civil penalties, while federal agencies like the FTC may take enforcement action. Beyond fines, mishandling SPI can trigger lawsuits, breach notifications, and long-term damage to brand trust.

Some parts of employee records may include SPI, such as health status, biometrics, racial or ethnic data, or union membership. While general HR data like job titles or salary isn’t classified as sensitive, businesses must apply heightened protections to SPI components in compliance with GDPR, CPRA, and labour laws.

Anonymised data is irreversibly stripped of identifiers, making re-identification impossible, while pseudonymized data replaces identifiers with codes but still allows re-linking. Only truly anonymised SPI falls outside data protection laws. Pseudonymized data is still regulated and must be secured to prevent re-identification, especially when combined with other datasets.

United Kingdom

24 Holborn Viaduct

London, EC1A 2BN

Get our monthly newsletter with insightful blogs and industry news

By clicking “Subcribe” I agree Terms and Conditions

Seers Group © 2026 All Rights Reserved

Terms of use | Privacy policy | Cookie Policy | Sitemap | Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information.